The siege of Charleston - 587 days

The Siege of Charleston, South Carolina, was one of the longest and most grueling campaigns of the American Civil War. From July 1863 to February 1865, Union forces worked to capture the symbolic heart of the Confederacy—the very city where the first shots of the war had been fired at Fort Sumter.

After the failed frontal assaults on Charleston’s defenses—most notably the bloody Battle of Fort Wagner in July 1863, where the 54th Massachusetts Infantry (an African American regiment) fought bravely—Union commanders shifted strategy. Rather than take Charleston by direct attack, they began a methodical siege, tightening their grip over time.

Union forces, under Major General Quincy A. Gillmore and later General William T. Sherman, established batteries on Morris Island and began bombarding Fort Sumter and Charleston itself. The “Swamp Angel,” a massive artillery piece placed in the marshes, famously shelled the city from a distance of over four miles, causing shock and outrage among Confederate civilians. Though Sumter was reduced to rubble, the Confederate flag remained flying, a symbol of Southern defiance.

Inside Charleston, the situation grew increasingly dire. Shells rained down on the city day and night. Civilians lived in fear, hiding in basements or fleeing to the countryside. Fires broke out frequently, destroying homes and historic churches. Meanwhile, disease and shortages spread through the civilian population and Confederate troops alike.

Confederate forces, under General P.G.T. Beauregard and later General William Hardee, were determined to hold Charleston at all costs. They reinforced the city's defenses with an intricate system of fortifications, mines in the harbor, and sunken ships designed to block Union access. Forts Moultrie, Johnson, and Sumter formed a defensive triangle guarding the harbor’s entrance, supported by batteries on Sullivan’s and James Islands.

Despite the suffering and devastation, Charleston did not fall through direct assault. The final chapter came as part of General Sherman’s infamous “March to the Sea.” After capturing Savannah in December 1864, Sherman turned north into South Carolina in early 1865. Facing the threat of being surrounded and cut off from the rest of the Confederate Army, Charleston’s defenders evacuated the city on February 17, 1865.

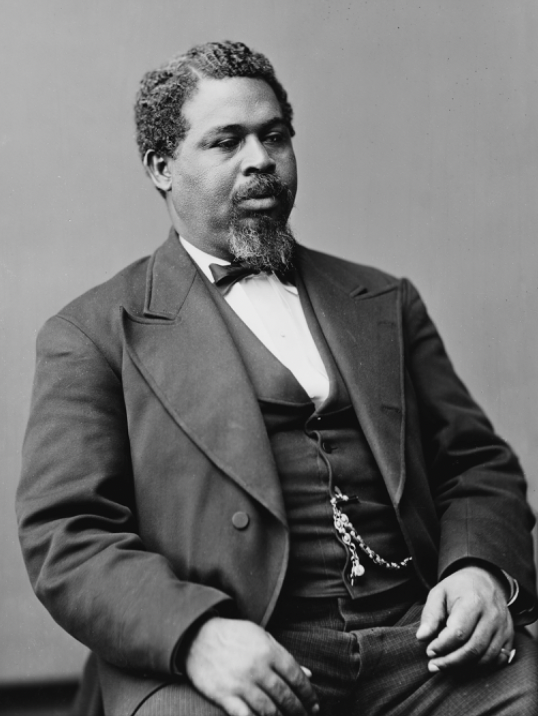

When Union forces entered the next day, they found much of the city in flames—Confederates had set fire to cotton stores before retreating, and the fire had spread. Despite the destruction, Union troops, including members of the U.S. Colored Troops, raised the American flag over Fort Sumter once again.

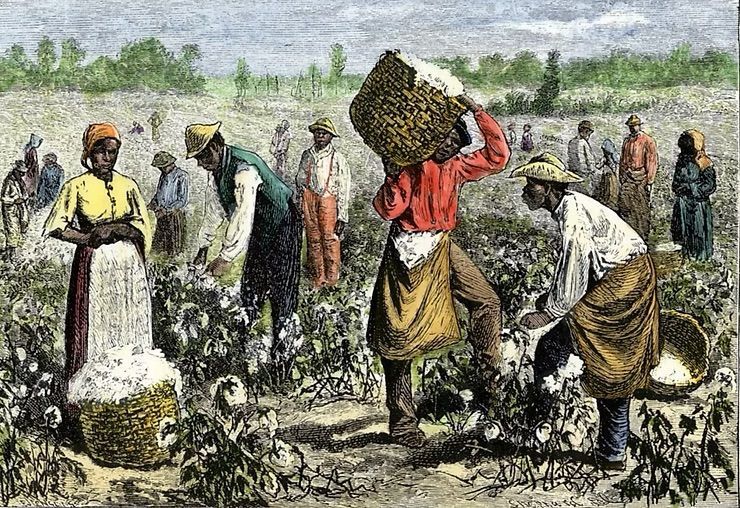

The siege had lasted 587 days. Though slow and grinding, it was a strategic Union victory that helped tighten the noose around the Confederacy in its final months. Charleston, once a proud and prosperous city, was left scarred—physically, economically, and emotionally.

The fall of Charleston marked not only the collapse of one of the South’s most iconic cities, but also the symbolic unraveling of the rebellion that had begun there four years earlier.